One of the noblest and most tragic figures of the imagination was the vampire-- damn his soul, and our own. But to see this marvelous, terrifying creature reduced to a plastic Halloween mask for sexual or political repression has been a tedious outrage. The vampire attained his stature through the emotion of fear of a fantastic evil, yet how utterly he has lost it all at the heavy, hammering hands of explication. Rest in peace, Nosferatu, none will ever take your place.So writes Thomas Ligotti, in the essay "The Dark Beauty of Unheard-Of Horrors." I don't necessarily agree that the evolution of the vampire in horror fiction has been a lamentable phenomenon-- that's a subject worthy of separate discussion. But I think it's undeniably true that the vampire, once the other, has become us. Like many monsters, it's now as much a tool for writing metaphorically about human psychology as an expression of truly alien malevolence. Forbidden love, world-weary philosophy, emotional cruelty: all can be "vampirized." This gives the basic vampire myth, which (as Ligotti notes elsewhere in his essay) can feel stale and over-explained, new potential, new variety. Just what a group of gifted writers can do with that potential is amply demonstrated by Teeth, the new vampire anthology edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling.

In marketing terms, Teeth is a YA anthology, but like most intelligent YA fiction it can be enjoyed by readers of any age, and the contributor list is similar to those of other Datlow and/or Windling anthos. Really, the only thing that sets this apart from "adult" anthologies is that most of the stories have teen protagonists. Inevitably, YA plus vampire will make some of you think of the Twilight series. I haven't read those books, but I know enough about them to reassure anyone with doubts that this anthology is something altogether different. Vampire romance is featured in only a few of these stories, and when it does, it always comes with a surprising twist.

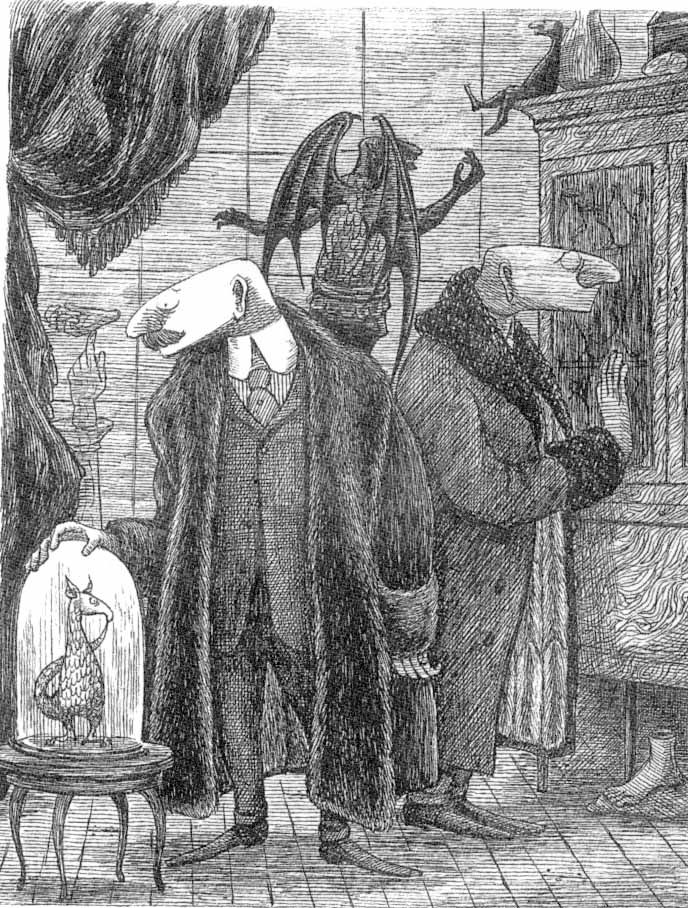

What do these stories offer, if not romance? Well, just about everything else. There are old vampires, young vampires, and vampires of unguessable age; good, evil, and morally ambiguous vampires; vampires in night school, vampires who collect antiques, vampires at the circus. Even when there are broad similarities in theme between particular stories, the variation in detail is more than enough to render the similarity irrelevant. Both "Gap Year" by Christopher Barzak and "In the Future When All's Well" by the astonishingly versatile Catherynne M. Valente use vampirism to explore the uncertainties about oneself and one's future that come at the end of high school. But they write about very different kinds of vampire, and in very different styles (Valente's story is in the first person, and does a pitch-perfect job of capturing a teenager's voice without caricaturing it), to a point where comparing them feels pointless.

Fairly or not, I think of YA fiction as often playing it safe, offering the moral lessons adults want teens to take rather than ones that are actually accurate. That's not the case here. Several stories are very adult and dark; they have, well, teeth. Sometimes the tropes of lesser fiction are turned on their heads to disturbing effect, as in Garth Nix's "Vampire Weather," which looks like it's going in the obvious direction and then doesn't. But this isn't an entirely dark set of stories: there's heroism, optimism, and even humorous asides, as in Cassandra Clare and Holly Black's "The Perfect Dinner Party," which contrasts tips for ideal party-giving with the events of a very unusual evening.

All the stories in Teeth are at the very least well-written and easy to read, with some spark of originality that makes it clear why they were published. Even where I thought the basic concept was too familiar or too obvious, there was a detail or a sentence or a character that made it all worthwhile. This baseline of quality is what I've come to expect from Windling and Datlow; it's the reason I'll buy any anthology of theirs, regardless of the authors involved. This time around, my own favorites, in addition to "Vampire Weather" and "In the Future When All's Well," were "Sunbleached" by Nathan Ballingrud, a spare but poetic story about a home broken both literally and figuratively, and the vampire that lives underneath it; Kathe Koja's "Baby," a chilling narrative that brought out in me an unexpected sympathy; and "History" by Ellen Kushner, a gently melancholy piece that features a very different kind of vampire romance from the hot and sparkly variety.

As Datlow and Windling's introduction reminds us, vampires stories have existed for a long time in a great many different places. Every time a popular new vampire concept emerges and spawns a thousand imitators, it's easy to decide that the blood-suckers are finally played out. But as long as there are humans, there will always be dark and unusual aspects of our existence to explore, and the vampire will surely remain an excellent way of doing that. No matter how many vampire stories are told, there will always be room for good new ones, and Teeth offers its readers nineteen of them in one inexpensive package.

* * *